Manga Manga!

The art of Japanese comic-strips

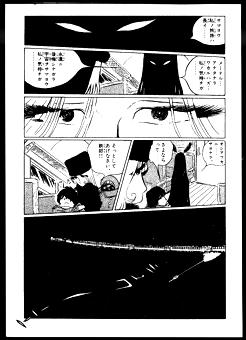

Leiji Matsumoto, Galaxy Express, 1999

With the exhibition Manga Manga! the Kunsthal introduces Dutch

museum visitors to a Japanese phenomenon. Immensely popular in

Japan. these comics have been available in Europe for some years

now in specialist shops. The Japanese are definitely the world's

most avid comic-strip consumers. Manga is a collective term for

comic magazines, newspaper strip cartoons and the bulky anthologies

of comics which often take up half the space in bookshops. Manga

accounts for almost 40% of Japanese magazine and book sales.

The popular weekly strip 'Shònen Jump' sells up to 4 million

copies. Newspaper kiosks are bursting with manga. and there are

even automatic vending machines for the real manga addicts. Manga

is big business. and there are thousands of cartoonists in Japan

to satisfy the vast demand. Many of them as rich and famous as

pop stars. Annual prizes are awarded: newspapers publish reviews

and serious appraisals. The kunsthal show presents a selection

of the prolific manga production from 1945 to the present. Most

of the 145 open books. accompanied by Dutch translations, contain

short manga stories and act as an introduction into the development.

dissemination and cultural background of the phenomenon. A Japanese

manga is rarely a slim book: a weekly comic is often as thick

as a telephone directory and contains short stories as well as

long-running series. Manga caters to the needs of every generation.

an English caption on the cover indicating the target-group,

for instance 'Lady's Comic'. 'Comic for Business Boys' or 'Exciting

Comic for Men'. The series are often subsequently published in

books whose thousands of pages fill several volumes.

Manga acquired its present form after World War Two as the result

of industrialisation and urbanisation in Japan and the rise of

mass culture. Manga is an important leisure activity in Japan's

collectively organised and highly disciplined society. Comics

are easier to read than a novel, they occupy less space than

a TV set and are not a disturbance to anyone else. The Japanese

are fast readers - it takes them 20 minutes on average to finish

a 320-page book. less than 4 seconds a page. It is hard to imagine

life without manga. which has penetrated TV programmes. computer

games. toys. contemporary art and history text-books.

Film tricks

Manga drawings are unambiguous. linear. black-and-white (colour

is rarely used) and virtually without shadow effects. The long

strips make copious use of visual inventions. Film techniques

are common and include perspectives involving the reader in the

action, close-ups. unusual angles. fade-in and fade-out. montage

and varying the number of frames to prolong a scene. Quite often

there are no text-balloons for several pages. images sufficing

to convey the story. In 'Kazure Okami' (Wolf and Child) a Samurai

classic. sword-fights can go on for 30 pages. the only 'sound'

being the clashing of steel. Abundant use is made of such 'sound-effects':

other examples are the impact of a fist on a chin ('POW! ') or

noodles being gobbled

('SURU SURU').

Over the years a variety of easy-to-understand conventions have

been established. The passing of time is indicated by a picture

of a rising or setting sun. a change of location by a telephone

pole or the facade of a building.

Buddha. money. sex and violence

There are manga for every target-group and on every conceivable

subject. Boys like a mix of excitement and humour. a preference

catered to by manga about sport. adventure. ghosts. science fiction.

school life and (smutty) jokes. For girls the emphasis is on

stories and idealised love: the stylised heroes and heroines

often have a western look. 'Shònen Manga' is the most

popular comic for boys. 'Shòjo Manga' for girls. The 350-page

weekly editions contain 15 stories. some of them complete. others

episodes from a series. The cover and first pages are in colour.

the rest in black-and-white.

Adult manga range from religion to adventure, from history to

pornography. Most are undemanding:

amusement is paramount. Wild scenes with violence. sex and obscenities

abound. The artists. often self-taught. have few literary ambitions.

Accordingly. many strips are ineptly designed and sheer trash.

There are however quite serious 'jitsuma manga' (practical comics)

and 'benkyo manga' (study strips) too, their themes ranging from

high school to international finance. A tendency towards more

intellectual manga can also be observed. Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989).

one of the best-known manga artists. drew the life of Buddha.

and Reiji Matsumoto (1938) made a successful manga about the

life of a poor student waiting to be admitted to university.

Ideograms

From a western point of view, the Japanese read the wrong way

round. i.e. from right to left. The texts are usually printed

vertically in the balloons and are read from top to bottom and

from right to left. There are four notation systems in Japanese;

used in combination. they can help create a special atmosphere.

For example. a Chinese personage might be given angular ideograms.

while a westerner's text might be written in the horizontal katakana

script reserved for borrowings from other languages.

Manga's success may well have something to do with the visual

script of the Japanese. The frequently used ideograms derive

from the Chinese, and were less abstract in the past. Manga also

has links with traditional Japanese art forms such as emakimono,

12th-century scrolls. and the popular books combining pictures

and text which were published from the 17th century on.

|